I’m a Boomer. My generation was born in the aftermath of the Second World War. Dachau and Auschwitz were not long ago historical events to us. When I first became aware of the Holocaust, the concentration camps of Europe were closer in time than the attacks of 9/11 are today. Back then, in New York, it was not unusual to catch a glimpse of a blurring number tattooed on someone’s forearm. It was not necessarily an elderly arm, either.

For my generation, the establishment of Israel was an inspiring story. One of the biggest novels of the era was Exodus. We learned about Israel as the triumph of a people who might not have survived in any European country if things had gone differently, which they very nearly did.

For many, probably most, educated people my age, the idea that millions of people in the US and Europe who describe themselves liberal or progressive, would instinctively respond to a news of pogrom that killed fifteen hundred Jews, specifically because they were Jews, with what amounts to a cry of “Go Palestine!” was literally unthinkable. It definitely caught me by surprise to hear people of goodwill publicly cheer a pogrom.

We have to think about what has brought us to this.

As a Practical Matter

How we got here is not easy to understand without knowing how little many Americans know about European and Middle Eastern history and geography. Most Americans live a very long way from anything that isn’t either more America, or looks just like it. For most of us, Mexico and a few islands in the Caribbean are the only such places within thousands of miles, and you can be 2,500 miles from Mexico without leaving the lower 48 states–that’s 4,000 kilometers. For scale, from Paris to Moscow is only 2,800 kilometers. Almost all of Europe, including Madrid, London, Stockholm, Leningrad, and Moscow is closer to Israel than Eastport, Maine is to Mexico. The distance From Eastport to San Diego, California is about the same as the distance from Berlin to Kabul, Afghanistan.

Consequently, as a group, Americans don’t pay a great deal of attention to world affairs.

With no disrespect to my fellow Americans, most of us have absolutely no idea what it’s all about in the Middle East, nor could we say confidently what millennium any of the countries of Israel, Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Egypt, or Iraq date from.

The Story of Israel and Palestine

The full history of Israel and Palestine would fill a library, and getting everyone to agree would probably require a war.

But we don’t really need that. Most of us only need enough to be able to read the newspaper. Accordingly, here is a very simplified history of the Israel/Palestine situation consisting only of factual information that can be readily verified or disputed by Googling, checking Wikipedia, etc.

The European Jews

From time immemorial until the last years of the 18th Century, all across Europe Jews had traditionally been banned from many occupations, required to live in restricted areas, excluded from political life, barred from schools and universities, and almost entirely excluded from gentile society. It was a degree of social exclusion roughly but not exactly comparable to that endured by African Americans from the post-Civil War era to the civil rights legislation of the 1960’s.

Pogroms, i.e. events of mass violence against Jewish communities, were common in the middle ages, and remained common in Eastern Europe even through the 19th Century. The last major pogrom before the World Wars took place in 1903 in Moldova. (There were also pogroms during and after the Second World War in Eastern Europe.)

The emancipation of European Jewry began with the French Revolution (1789) but proceeded more slowly outside of France and the other areas that fell under Napoleon’s control after the revolution.

In Britain, The Jewish Disabilities Bill of 1848 first allowed Jews to hold public office, and their emancipation largely completed by 1871. In the countries that would be unified as Germany in 1871, progress was similar. Emancipation got started incrementally somewhat earlier in some of the polities that would ultimately be amalgamated into Germany in 1871. The process got started in the early 19th Century, with serious proposals of religious equality across Germany coming with the revolution of 1848, and formal equality arriving in 1871 under the unified Germany’s constitution.

By the middle of the 19th Century, even before Jews were formally admitted to European society, there was already a burgeoning Jewish intelligentsia publishing in the national languages of Europe as well as in Yiddish, which was widely spoken across national boundaries. A measure of the extraordinary rapidity of Jewish advancement in Europe is that many of the greatest minds of the early 20th Century were Jews born in the aftermath of the revolutions of 1848. Sigmund Freud was born in 1856, Albert Einstein in 1879, and Fritz Haber in 1876. Within a generation of their admission to European universities, the Jews were already punching far above their weight across the European intellectual world.

The Dawn of Zionism

Along with the powerful Jewish current of assimilation ran a countercurrent of Jewish nationalism. The Zionist movement, embodied in the World Zionist Organization, was founded in 1897 following the publication of Der Judenstaat, i.e., The Jewish State by Theodor Herzl. The movement would spread far beyond Germany, catching on among many, but by no means all, Jews worldwide. At the time, the land that would later become Palestine had a relatively modest Jewish population, approximately five or six percent, with the majority of the remaining people being Muslim. There were numerous other groups as well.

The Ottoman Empire and Palestine

The Ottoman Empire, aka The Turkish Empire, at its peak, dominated the shores of the Mediterranean from Algeria, east across the width of North Africa, up the coast of the Middle East, west across Turkey all the way to Greece, up the Adriatic to the Balkans all the way through Croatia to the border of modern Slovenia. The Empire ran from Hungary and Romania to the border of Iran. It also included the Red Sea coast of the Arabian peninsula all the way to the Gulf of Aden, and on the east side of the peninsula it included Iraq, Kuwait and a smattering of other areas on the Persian Gulf.

Once one of the mightiest empires in history, by the early 20th Century, the Ottoman Empire was staggering, known as “The Sick Man of Europe”. It survived the First World War, barely, critically weakened by its own internal failures of governance and by the rising nationalism among its countless constituent nationalities.

The collapse of the empire was hastened by the connivance of the British, Russians, and French, who saw it as a threat to their interests in the Middle East. Both before and during the war, the British made side deals with various Ottoman possessions in support of their independence movements, and in 1916, Britain signed the Sykes-Picot Agreement with France regarding how to divide the spoils of the Ottoman Empire when the war ended.

One notable element of the foreign meddling in the Ottoman Empire was the 1917 (one year before the end of the First World War) British issuance of the Balfour Declaration, one of the most important documents in history of the modern Middle East. This document expressed Britain’s support for the establishment of “a national home for the Jewish People” in what would become Palestine. This was an open expression of British commitment to the Zionists. At the time, Britain was still the largest and most powerful empire in the world.

A Tricky Point

The provenance of the name Palestine is a touchy subject.

The name Palestine has existed since ancient times, being a slight variation on Philistine, the name of a people who are believed to have arrived in the Middle East in the Late Bronze Age, sometime around the 12th C. BCE.

Over many periods of history, the derived name, Palestine, has often used to describe the region, but it is important to note that it was never until the mid-Twentieth Century, the name of a political entity. The closest it had come to that is its inclusion is in the name of the Ancient Roman province of Syria-Palestina, a much larger entity. The distinction is important because, although the ancient Philistines were a people, the derived name, Palestine, has traditionally been used to describe only the region, which contains numerous peoples including, but not limited to, several distinct sects or subdivisions of each of the major religions, Muslim, Christians, and Jews, plus Druze, and other groups.

The area fell under Muslim control early in the history of Islam in the Seventh Century, was partly under European Christian control off and on in the Middle Ages from the Eleventh to the Thirteenth Centuries. From 1516 to the end of the First World War, along with almost all of the modern countries of the Middle East, it was an Ottoman Empire possession, part of the larger administrative area of Syria. It was not, during those centuries, a separate province or region even within the Ottoman Empire.

The use of the name Palestine in its modern sense started with The British Mandate in 1920. For the first time, Palestine represented a political entity, although not always a country (see below.)

Palestinian did not, during the Mandate years, refer a specifically Arab ethnicity, and properly speaking, does not now, although sloppy use of the word to mean Arab Muslims from that area is increasingly common today.

This is not a technicality. Arab and Muslim are not the same. For one thing, Arabs in Palestine could be also be Christians, Jews, Druze, Samaritans, and Baha’i Faith. (Jews who originated from the Middle East and North Africa are known as Mizrahi.) Christians of Middle Eastern origin have been in the area since the First Century CE, half a millennium before Islam began. Also, not all residents of Palestine were ethnic Arabs. Other peoples, notably people of European origin, both Jews and Christians, had lived there for centuries, in addition to a demographic of more recently immigrated Jews, primarily but far from exclusively, Ashkenazi Jews from Europe.

The British Mandate over Palestine

In the aftermath of the war, with the ongoing collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the task of carving up of the possessions of the failing empire fell to the new League of Nations. In 1920, the League of Nations granted Britain an administrative “Mandate over Palestine”. This was one of several mandated fragments of the Ottoman Empire including the Iraq Mandate, the Syria and Lebanon Mandate, and the Transjordan Mandate.

Many Americans will not realize how young all of the countries of the Middle East are. Many of the names have ancient histories, but they had not been independent countries in centuries, if ever. These mandates made either Britain or France, as victors in The First World War, temporary custodians of these regions of the moribund empire. The Mandate powers did not own the mandated areas, but were appointed to be responsible for them until their status could be regularized. (Other post-war geographical entities in Europe had mandates as well, not just former Ottoman territories.)

This period, 1920 to 1948, is the first time in history that the name Palestine referred to a political entity that possessed a government of its own. For the period of the mandate, the final authority was Britain, but a Palestinian government was quickly set up and Palestine increasingly functioned as a country as time passed. Documents from the period are an indication: for the first part of the Mandate period, passports of people who moved to Mandated Palestine were issued by Britain, and native born Palestinians got a “Provisional Certificate of Palestinian Citizenship” from the Palestine Government. Subsequently, from 1925 to 1948, Palestinian passports were issued directly by the Palestine government.

Note that for the early part of the mandate period, the Ottoman Empire still existed. The end of the the Ottoman Empire was a complex, drawn out affair, but it was given the coup de grace in 1922, four years after the end of the First World War, with the abolition of the Ottoman Sultanate, when Kamal Ataturk’s revolutionaries seized power in The Turkish War of Independence.

Through the 1920’s and 1940’s, under British control, immigration of Jews into mandated Palestine greatly increased, with Jews throughout Europe and elsewhere buying property in Palestine. Note that this period spans the time from just after the First World War, to just after the Second World War, and includes the entirety of the Holocaust period.

Post Second World War

With the end of The Second World War in 1946, there was widespread desire by Jews and others for a Jewish homeland in Palestine, and Jewish immigration accelerated rapidly. By this time, the Jews were a majority in about half of Mandated Palestine, with Arabs a greater majority in the other half of the area.

Zionism was an expression of a trans-national kind of nationalism, a political/cultural movement of a people whose cultural and historical identity was primarily attached to the Holy Land, rather than specifically to the new almost-a-country of Palestine. By the post-war period, the majority of the Jews in Palestine were no longer of native ethnic origin, but were of European or Russian extraction, immigrants, the children of immigrants, or the grandchildren of immigrants. They were legitimate Palestinians, but an immigrant culture, much as naturalized Pakistani British are British, or naturalized citizens of the United States from Mexico or Cuba are Americans.

The Palestinian Arabs had a growing nationalism of their own. Although a larger percentage of Muslim Arabs than Jews had roots in the area going back many generations, a specifically Palestinian identity was new for them as well. For the Arab Palestinians, the idea of “Palestinian” began to evolve from being a new nationality to being an ethic identity.

Both peoples saw Palestine in emotional, nationalistic terms, and the views of both groups were arguably imperfect. Zionism had been proceeding since before the turn of the century with the long-term project of building a Jewish homeland through legal economic means, most importantly, through immigration, and they had done so with at least tacit support from the European powers. The Palestinian Jews at that point were by no means all fresh off the boat; Zionist-motivated immigration had been going on for almost three generations by then, and by the post-war years, not only had many of the “European” Jews been born in Palestine, often so had their parents.

Palestinian nationalism developed approximately in parallel with Zionism, but got off the ground later because Palestine wasn’t a separate entity until the mandate, while Zionism as a movement with a name had existed for a generation at the time of the mandate. The Palestinian Nationalism was not initially specifically Arab, but became increasingly Arab and Islamist as the number of Jews increased and the intention of the Jews to set up a Jewish homeland, as distinct from a Palestinian state, became more clear. Other groups, such as Palestinian Christians existed, and still exist today, but primary players were the Jews and the Muslim Arabs.

The League of Nations was succeeded by the United Nations at the end of The Second World War in 1945, when the mandate was 25 years old. Acknowledging the reality of distinct Jewish-dominated and Arab-dominated areas within the mandated Palestine, in 1947, the United Nations proposed separate Jewish and Arab states, plus a third entity, Jerusalem, which would be administered by the United Nations.

The West Bank

At this point, it is necessary to be clear about what the West Bank is.

The Jordan River separated Mandated TransJordan, subsequently just Transjordan (Transjordan means “across the Jordan”), from the Mandated Palestine territories, to the west, along its length, down to the Dead Sea, where the river terminates. From there, the border between Transjordan and the Mandated Palestine ran down the middle of the Dead Sea. After the southern end of the Dead Sea, the border was not marked by any particular geographic feature, but ran all the way to almost the southern end of the Mandated Palestine at the Gulf of Aqaba, where today, Israel, Jordan, the Sinai Peninsula (Egypt) and Saudi Arabia, almost come together.

Modern Israel shares a border with Jordan on the Jordan River for only fifteen miles or so near the northern end of Israel, just south of the Sea of Galilee, which is close to where Jordan, Israel, and Syria come together.

What is known as the West Bank, starts at the southern end of that short shared stretch of river, and takes up about 2/3 of the east/west width of the original Mandated territories all the way to roughly the southern end of the Dead Sea, minus a triangular chop, missing to include half of the holy city of Jerusalem from the Israeli side.

The word “bank” is misleading. It makes it sound like the West Bank is a narrow strip along the river, but it’s the opposite. To the west of the West Bank, Israel is a relatively narrow strip along the Mediterranean. The much wider chunk of land between Israel and the Jordan River is the West Bank.

the West Bank was the heart of the mandated Palestinian land that was earmarked for the Arab state in the United Nations plan. Gaza was another part. There were numerous snips of other territory, but the real meat of what was to be the Arab state was the West Bank.

Statehood and The First War

On May 14, 1948, the territories in the Jewish part of the mandate, under David Ben-Gurion, accepted the United Nations partition plan, and in the face of the Arab rejection of the plan, David Ben-Gurion declared the Israel an independent country, following the withdrawal of British forces.

The Arabs in the mandate territories, as well as the surrounding Arab states, were emphatic in their rejection of the plan, being opposed on principle to the idea of creating a Jewish state on what they regarded as Arab land. In addition to the rejection on principle, they also saw the specific partitioning as unjust, because the proposed Jewish part would include some areas that were majority Arab.

The positions of the two sides were clear, incompatible, and not subject to compromise. The Jews wanted the creation of a Jewish state in part of Palestine, and the Arabs rejected the idea, insisting on a single Arab state comprising all of Palestine.

The day following the founding of Israel, May 15, 1948, the neighboring Arab states of Egypt, Transjordan, and Syria, plus troops from Iraq and Lebanon, attacked the new state of Israel. Transjordan immediately charged into the West Bank, occupying it, ostensibly to keep it safe for the Palestinians.

The war was a short one. Astonishingly, with only one day of being a country behind her, Israel fought an eight month war and was victorious against her combined neighbors.

Under the terms of the armistice, the borders of Israel came out somewhat more favorably than the original territories defined by the United Nations plan had been, including placing the Gaza strip, which had formerly been under Egyptian control, under Israeli control, and adding to Israel a number of small areas that had been Arab under the original plan. The most important of these additions was a wedge into the side of the West Bank that gave half of Jerusalem at the apex of the wedge to Israel.

Israel came out of the war somewhat better off, but Transjordan was the big (temporary) beneficiary. Transjordan had annexed the occupied West Bank, seizing what was by far the most important part of the Mandated Palestine that might have one day been an Arab Palestinian state, including Nablus to the North, and Hebron to the South, and East Jerusalem. Transjordan quickly made it clear that the occupation of the West Bank was not just a strategic move, but was in fact intended to be a permanent annexation.

With the West Bank now officially part of Transjordan, Jordan was no longer “across the Jordan river”, but straddling it, so the name was officially changed to The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. Cravenly, the British, Americans, and Pakistan accepted the annexation, with the Arab League protesting, but it quickly became a done deal. It would not be unfair to think of this as massive treachery to the Arab Palestinians by Jordan, abetted by the Europeans.

The Arabs Palestinians, having rejected the original UN partitioning and gone to war to seize the whole of Palestine were the losers. If it had gone differently, and Israel had taken the West Bank, they would have had a good chance of seeing a return to something like the original partition plan some day after tempers cooled, but with their so-called ally Jordan having annexed the heart of Arab Palestine, they no longer had the makings of an independent country.

Arab Palestine wasn’t the only one who got done dirty by Jordan in the aftermath of the 1948 war. The original two-state proposal, as well as the armistice after the 1948 war, had specified that Jerusalem would remain open to all. However, under Jordanian control, East Jerusalem, the important part from the point of view of the Jews, was closed to the Jews, and numerous Jewish holy places were desecrated and destroyed. Even tourists visiting Jerusalem were henceforth required to have papers proving they were not Jewish.

Jordan, an expansionist power in the region in those early days, remained a staunch enemy of Israel, and a simmering guerrilla war festered between the former Palestinians of the now Jordanian West Bank and the Israelis.

Keep In Mind

It is important to remember, that at this point in history, all of these countries that originated with mandates were very young. If they were people, three would be Boomers, and two would be only slightly slightly too old for that honor, one of them missing it by only three years.

Iraq was the old timer, having become independent of the Mandate in 1932. Lebanon became independent of the French Mandate in 1943. Syria became independent of the French mandate in 1946. Transjordan also became independent of the British Mandate in 1946. Israel was last, shaking off the British Mandate in 1948.

The only country that made war on Israel that had not been a Mandate territory was Egypt, which was relinquished by the Ottoman Empire during the First World War, becoming a nominally independent country that was only symbolically linked to the Ottoman Empire.

While nominally the first of the Middle Eastern possessions of the Ottoman Empire to become independent, in some ways, it was also the last. (Strictly speaking, only a little bit of Egypt–the Sinai–is actually in the Middle East. The rest is in Africa.) After its nominal independence, the British continued to pull the strings in Egypt until well after the Second World War, so Egypt’s true independence really only fully took hold after after the Mandate countries had already come into their own. Egypt shook off its monarchy in the Egyptian Revolution of 1952, establishing the Republic of Egypt, but did not fully free itself from British and French domination until 1956, when they nationalized the Suez Canal under Gamal Abdel Nasser.

The Second War

In 1956, the same year that Egypt nationalized the Suez Canal, they closed the Straight of Tiran to Israeli shipping. The Straight is the narrow southern opening of the Gulf of Aqaba, the long body of water that separates the east side of the Sinai Peninsula and the Arabian Peninsula. That body of water connects Israel to the Red Sea, thence to the Gulf of Aden, and beyond that, to the Indian Ocean. The Straight is actually about 100 miles from Israel, with Egypt on one side and Saudi Arabia on the other. However, it is indispensable for Israel’s economic survival because it is the route by which most of Israel’s oil is imported.

The Sinai Peninsula has three other sides. It has a stretch of Mediterranean coast; a long, mostly straight, and almost uninhabited border with Israel; on the side opposite the Gulf of Aqaba, are the Gulf of Suez and the Suez canal, which connect the Mediterranean to the Red Sea at a point not far from the Straight of Tiran.

Closing the Straight of Tiran was viewed as an existential threat by Israel, which Israel made clear to Egypt. Accordingly, they briefly invaded Egypt, together with the United Kingdom and France. A settlement was quickly reached, the Straight opened, and a United Nations Emergency Force was left in the region as peacekeepers.

The Third War: 1967 The Six Day War

In 1967, eleven years later, Egypt, under Nasser, again closed the Straight of Tiran to Israeli shipping. This was the same action that had been the casus belli in 1956. In recognition that their actions were tantamount to a declaration of war on Israel, the Egyptians mobilized their military forces on the Israeli border, and ordered the United Nations Emergency Force out of the country.

Israel responded with a surprise preemptive attack, absolutely devastating the Egyptian air capabilities and ground forces, and simultaneously launching a ground invasion of the Sinai peninsula.

That the Israeli attack was a surprise is remarkable, but somehow, they caught the Egyptians flatfooted, despite Egypt being in a state of military mobilization. Syria and Jordan jumped in as allies of Egypt, but the war was over in six days, with Israel the hands-down winner.

In the brief course of the war, Israel seized the West Bank from Jordan, making the Jordan River the new de-facto border with Jordan.

Israel also seized the Golan Heights, a key strategic feature that separates Israel and Syria in the far north. The Golan Heights is not a large area, but it is of great importance, as it offers a commanding artillery position in either direction to the side that holds it.

Israel also seized the entire Sinai Peninsula from Egypt, making Egypt a one-continent country.

The word that best characterizes the reaction of both the Middle East and the European/American powers to the outcome of the war is “gobsmacked.” Israel had a population of approximately 2.8 million people at the time, about as many as Brooklyn NY. The Arab combatants had a combined population 14 times greater–about forty million. Israel lost 776 soldiers plus a few hundred civilian casualties, while Egypt saw 10,000 to 15,000 killed, Jordan 6,000 to 10,000, and Syria 1,000 to 2,500. The war was over in about as long as it would take to tour the conquered territories by car.

The West Bank

Semantics are important in understanding the complex relationship between Israel and the West Bank. On the day after Israeli independence in 1948, Israel’s neighbors had attacked, and Transjordan seized the West Bank, but they did not seize it from Israel, which had made no claim on it. They seized it from their own supposed ally, Arab Palestine, i.e., the part of Palestine that had not gone along with the two-state partition proposed by the United Nations.

Despite being on the losing side in the 1948 war, Transjordan succeeded in keeping the West Bank and incorporating it into what would shortly be renamed Jordan. There was no pretense that they were somehow just keeping it safe for the Arab Palestinians–they renamed their country to reflect that the West Bank would not be part of Jordan, nee Transjordan. The annexation that was recognized by the great powers.

This is critical, because, in 1967, the Israelis did not seize the West Bank from an existing country known as Palestine–there was no such country at that time. The West Bank had been part of Jordan for a generation, i.e., almost the entire time Israel had existed.

During that generation, Jordan had been an active enemy of Israel, allowing, in fact, encouraging, Palestinian nationalists to use it as launching pad for attacks against Israel. If that didn’t make Jordan’s enmity clear, they had also reneged upon the 1948 war’s armistice agreement to keep Jerusalem an open city, instead barring Jews from East Jerusalem and systematically destroying Jewish sites in their half of the city.

The Fourth War: The 1973 The Yom Kippur War

The region stabilized again for six years, until Yom Kippur 1973, when Egypt and Syria launched a surprise attack on Israel. This attack was a much closer run thing than the 1967 war. The Arabs had the initiative and took Israel by surprise, quickly exhausting the Israeli stocks of munitions. The United States, initially reluctant to help, jumped in with an emergency supply line after the Russians started supplying the Arabs. This was no small thing for the United States, as the help was given at the cost of enduring a devastating oil embargo by the oil-rich allies of Egypt and Syria.

Despite the unpromising start of the war, with supplies coming, the Israelis, under the young Ariel Sharon, who is his later years would become the prime minister, crossed the Suez and attacked the Egyptians from the rear, even as in the north the Israeli army repulsed the Syrians in the Golan Heights. That fight was very close–the Israeli defense nearly caved. The Israeli victory in the Golan Heights turned the tables, putting Israel in the position of potentially menacing Damascus when repeated calls for a cease fire by the UN brought hostilities to a close.

What Might Have Happened

The fate of Israel hung in the balance in the early days of the war. Israel, though it has never admitted it openly, is, and almost certainly was in 1973, a nuclear power. It is difficult to imagine that Israel would have allowed itself to be overrun by the Syrians had its defense of the Golan Heights failed. Israel was led by a generation that had survived Adolph Hitler. Arabs, Jews, and the rest of the world should be very glad that Israel was able to prevail with conventional weapons.

A Framework For Peace

The 1978 the Camp David Accords were a series of negotiations held under the auspices of United States President Jimmy Carter, bringing together Egypt, under Anwar Sadat, and Israel under Menachem Begin. This was no small achievement, because Sadat had been the architect of the 1973 attack on Israel.

The key component was the resolution of the Egypt-Israel conflict. This was embodied in the Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty, signed in Washington DC in 1979. It created diplomatic and economic relations between the two countries. Under the treaty, Israel agreed to withdraw from the Sinai, which occurred in stages, fully returning Sinai to Egypt in April 1982.

Apart from returning Sinai, without which it is difficult to imagine Egypt ever truly making peace with Israel, it meant that for the first time Israel and its most important neighbor would have true diplomatic relations, i.e., a means of settling differences without shooting at each other.

This milestone of peace occurred thirty years after Israel’s founding.

Lebanon 1982

Meanwhile, however, peace was not so close on Israel’s norther borders. Palestinian nationalists, primarily the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), had waged a more or less chronic guerrilla war on Israel from bases in southern Lebanon with the tacit approval of the Lebanese government.

In 1982, the same year that the Sinai was fully restored to Egyptian sovereignty, Israel launched a full-scale invasion of Lebanon to suppress the armed Palestinians.

This relatively small war was complex politically, and would have long consequences. Israel fought the PLO, Syrians, leftists, and Lebanese Muslim forces. The situation was particularly fraught because Lebanon was already engaged in a protracted civil war.

Lebanon is not as overwhelmingly Muslim as are Israel’s other neighbors. There are 18 recognized religions in Lebanon, and Maronite Christians are an important force, the country having been founded by an alliance of Maronites and Druze. (Druze is a less well known Abrahamic faith. Like Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, it traces its origins back to Abraham. It is sometimes described as an Islamic sect, but Druze themselves do not consider this to be the case. Like everything in the Middle East, it’s complicated.)

The Israelis fought in alliance with Lebanese Christian forces, who, at the risk of oversimplification, sought to weaken the hold of Palestinians and Syrians on southern Lebanon. In one of the most horrifying events of the war, Lebanese Christian militia, known as the Phalange, operating in concert with, but not actually accompanied by Israeli forces headed by Ariel Sharon, entered the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps in Beirut, and murdered somewhere between 500 and 3,500 civilians. It was an event that did great and lasting harm to Israel’s public image around the world.

The war was long, bloody, and had mixed success. This should not be surprising–Israel’s previous wars, all stunningly successful, had been against conventional uniformed military forces acting at the behest of governments. Guerrilla forces, though typically much less well equipped than a regular army, are harder to definitively beat because there is no government at the top that decides when a war is lost. Guerrilla movements endure because their armies can survive being beaten longer than most governments can maintain the political will to keep beating them.

Before the invasion, the Lebanese support for the Palestinians in the south was essentially passive. Had the country not been fragmented by civil war, they might not have tolerated it at all–it is impossible to know. But they did tolerate it, and Israel had been subjected to continuous harassment from that border region.

The unanticipated consequence of the 1982 invasion was the formation of Hezbollah (The Party of God), which emerged during the occupation. The Palestinian Arabs are predominately Sunni (although there are some Shiites.) Hezbollah, in contrast, is a Shia Muslim organization, both a political party in Lebanon and a terrorist organization supported in part by Iran, which is decidedly Shiite, and Syria, which, while predominately Sunni, has a Shiite faction that is strong in their government and security apparatus.

Shiite and Sunni Muslims have a somewhat fraught history with each other and do not always see each other as allies. The invasion of Lebanon had the unhappy effect of midwifing the birth of a strong Shiite enemy to the north that is partly of an official governmental nature, and partly a trans-national terrorist organization, with the drawbacks for Israel of both.

The Lebanon civil war, which started in 1975, ended in 1989, with Israel still occupying parts of Lebanon.

The invasion was a tarpit for Israel, with Israel occupying parts of Lebanon for 18 years, fully withdrawing only in 2000 without achieving the goal of extirpating the Palestinian fighters in Lebanon. If anything, the situation was worse when they left than it had been when they arrived.

Lebanon 2006

Hostilities erupted again in 2006 when Hezbollah captured two Israeli soldiers in a cross-border raid, to which Israel responded with a campaign known as the Second Lebanon War. The war lasted a little more than a month and ended in a UN-brokered cease-fire.

The UN placed the United Nations Interim Force In Lebanon (UNIFIL) to monitor the ceasefire, but Hezbollah has refused to disarm, and has since grown to be a powerful political force in Lebanon, and has become effectively a trans-national force aligned with Iran, backing Assad’s forces in the Syrian civil war and Hamas in Gaza.

The Settlements

The initial refusal by Palestinian Arabs to accept a two-state arrangement in 1947 would have presented a long-term difficult situation even without the war that immediately followed Israel’s declaration of statehood. Without that war, it is conceivable that in time, the Arab Palestinians might have shaken off their disappointment at not getting the whole of Palestine, and set up an Arab Palestinian state.

Transjordan’s annexation of the West Bank made the situation infinitely harder because it left an inadequate base for an Arab state. Arab nationalism wasn’t a single unified movement. Each individual country had its nationalists, but the Arab world as a whole had a sort of transcendent nationalism that could not abide a Jewish state in the heart of the Arab world. The Arab states had and to some extent, still have a stake in a two-state solution not working.

Another angle on this is that the neighboring states have not always been stable. Having a convenient enemy has a times been very useful for deflecting criticism that might otherwise land closer to home. For many of these states, there is no great upside to peace with Israel.

The end of the British Palestine Mandate had been spectacularly bad for all of the Arab Palestinians who where not Israeli citizens. Not only did they not get the whole enchilada, they didn’t get any state at all. By the time Jordan lost the West Bank to Israel in 1967, an entire generation of fanatically anti-Israel Palestinians had grown up, with Jordan actively encouraging anti-Israel terrorism out of the West Bank.

An outsider might say that 1967 seemed like the one golden moment in history when a two-state solution might yet be implemented. With the West Bank severed from Jordan, other than some snips that had become truly part of Israel after the 1948 armistice, almost all of the original mandated Palestinian territory was potentially available for an Arab Palestinian state.

The reasons that this didn’t happen are several.

One of the main reasons is that in 1947, the Jews (it wasn’t yet Israel) were very much in favor of a two-state solution, and voted for it. However, in the 19 years since then, Israel had been attacked repeatedly by coalitions of Arab states and Palestinian Arabs, who clearly and determinedly wanted her erased from the map.

In this context, the West Bank provided a very significant defensive depth between Israel and an historically hostile Jordan. It is easy for an outsider to lose geographic perspective about this; in places, a person can walk from the border of the West Bank to the Sea in two or three hours; at that point, Israel is less than twice the width of Manhattan Island; it is a distance a tank can traverse in five or ten minutes; artillery can shoot rounds into the sea from the West Bank. Fifty extra miles means a lot.

Another barrier was the fact that there wasn’t a clear party to negotiate such a settlement with. Jordan had long run the West Bank, and with them out of the picture, the only obvious group to negotiate with was the PLO, which opposed any two state solution, just as the Arab Palestinians had 19 years earlier. The PLO later came around to some degree, but they were not amenable at the time.

In addition to these practical matters, Israel had been attacked repeatedly and won. It would be surprising if they were immediately amenable to a plan that put Israel at increased risk, in order to benefit people who loudly and regularly called for their extermination.

Israel isn’t one uniform group that sits down, makes a decision, and then moves in lockstep. It is a country built by the kind of people who uproot themselves to come to a new land and carve out a nation. They aren’t necessarily that easy to manage. Sort of like herding cats.

Many Israelis began to move into the occupied territories and set up “settlements” in a popular move to make the West Bank Israeli by force of demographics, much as Israel itself had been created by immigration. To some degree, this has worked. In the years that followed, so many Israelis moved to the West Bank that the demographics of the land is changing. Religious Jews tend to have large families and their population is growing faster than the Arab population in the West Bank, although the land remains predominately Arab Muslim.

The settlements today are the most conspicuous barrier to a two-state solution, because while they remain a minority, there are now so many Jews living there that it is not clear that it is politically possible for Israel to force a stop to the settlement movement, or to turn the territory over to Arab rule, where the Jews would be subject to persecution. Settlement has made an already extraordinarily difficult situation, if possible, even more difficult and it remains to be seen whether it is politically possible to undo it.

Gaza

Like the West Bank, Gaza needs to be talked about separately.

As mentioned above, Gaza was part of the Mandate that was intended by both the League of Nations and the United Nations to be part of Arab Palestine under the two-state plan.

In the 1948 war, Egypt took over Gaza and retained control of it for the next 19 years. Many Palestinian Arabs displaced by the war went to Gaza as refugees and never returned. In this period, Gaza became a major homeland of Palestinian nationalist movements, notably the Palestine Liberation Organization, aka the PLO.

Gaza remained under Egyptian administration until the 1967 Six Day War, when Israel captured the territory.

Following the war, Israel occupied Gaza for the next 38 years, a period of endless conflict and tension between the Arab Gazans and the Israelis. The inherent tension caused by the Israeli occupation was greatly exacerbated by presence of Israeli settlements inside of Gaza.

In 2005, the Israelis unilaterally withdrew, dismantling the settlements, and leaving Gaza to the administration of the PLO, with the help of significant foreign aid. Yasser Arafat died in 2004 of causes that are not clear. Both stroke and murder by poisoning with polonium-210 are possible, but despite investigation, the truth has not definitely been established. Poisoning seems likely, but the mystery may never be satisfactorily resolved.

In the aftermath of Arafat’s death, the Hamas party won the legislative elections in Gaza, but a power struggle ensued between Hamas and Fatah, which administered Arab affairs in the West Bank. Hamas came out on top in a violent takeover in 2007, while Fatah remained in power in the West Bank.

Ongoing conflict with Hamas lead to a blockade on Gaza by Israel two years later in 2007, restricting movement of people and goods across the Israeli/Gaza border. Egypt also blockades Gaza in an effort to prevent the political chaos from spilling into Egypt. There is no doubt that the blockades have made life difficult in Gaza. All parties acknowledge this, but neither Israel nor Egypt want their borders open to the chaos.

Rockets and Tunnels

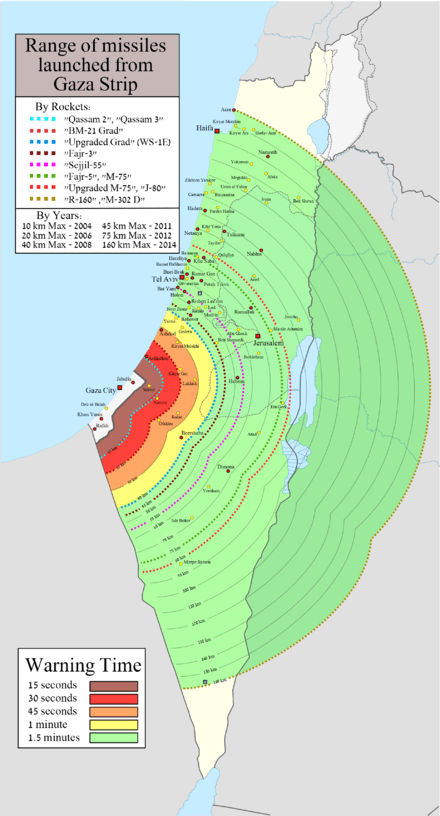

Hamas has made an ongoing practice of attacking Israel by rockets and mortar fire from within Gaza in the years since 2007. Relatively few rockets were fired prior to the beginning of Hamas rule. The rockets are primarily locally built from standardized designs using metal pipe, with sugar and fertilizer as fuel, and approximately a kilo of TNT as the warhead. Technologically, they are essentially metal skyrockets without guidance systems, but they are gradually becoming more sophisticated, with some of the modern versions being closer to military weapon standards. The number of rockets in an attack has been as few as 15, but attacks usually employ a thousand or more, and as many as 4,200 have been fired in a single attack. Almost nowhere in Israel is farther than 90 seconds flight time for a rocket.

During the period between 2007 and the present, Hamas has dug several hundred kilometers of tunnels. The tunnel program in Gaza was originally primarily for smuggling in people, goods, and military equipment, but has evolved to include an enormous internally oriented system of well engineered military infrastructure. One important use of the tunnels is to conceal and transport rockets.

The exact number of rockets that have been fired at Israel is not known, but it is greater than 20,000. They are not very useful militarily, but rather are primarily a terror weapon against civilians. They are a spectacular nuisance, and have a traumatic effect on Israelis subject to attack, but have killed relatively few Israelis, probably fewer than 100, while injuring a few thousand.

In response to the attacks, Israel has conducted major military operations against Gaza four times since 2007.

Operation Cast Lead (2008-2009) A three week conflict in response to rocket attacks.

Operation Pillar of Defense (2012) A one week conflict involving naval and air strikes in response to rocket attacks.

Operation Protective Edge (2014) A fifty day conflict that did more significant damage in Gaza, resulting in greater casualties and displacement of civilians in response to rocket attacks and the kidnapping and murder of three Israeli teenagers.

Unnamed Fighting (2018-2019) Throughout these years there were numerous smaller incidents of rocket attacks from Gaza that were responded to by Israeli airstrikes.

Hamas attack of October 7, 2023. Hamas attackers used bulldozers to break through the cordon of fences around Gaza and launched a large scale ground attack on Israeli civilians. The attack was supported by thousands of rockets, attackers arriving from the sea by boat, and fighters who were carried over border barriers by ultralight aircraft. The attack killed approximately 1,500 Israelis, mostly civilians, with horrifying atrocities that were publicized over the Internet. A large number of hostages were also taken back to Gaza. The Israeli response ongoing, with large scale air strikes and a major land invasion with the goal of suppressing Hamas and destroying the tunnel infrastructure.

PLO and Fatah

Who’s who in Arab Palestine politics can be confusing. The line between legitimate political party, military group, and terrorist organization is rarely clear and is to some extent, subjective. It also changes over time. Hamas, Hezbollah, and Fatah have all been everywhere on that continuum and have not all moved in the same direction over time.

Fatah is was founded in the late 1950’s to fight Israel, which by then was almost a decade old. Early on, they were generally regarded as a terrorist group, rather than a political organization, and were responsible for major attacks on Israel both at home and abroad. Yasser Arafat was the original leader of Fatah.

In 1964, Arafat founded the PLO to function as an umbrella organization for Fatah and numerous other Arab Palestinian organizations, and to have a greater and more legitimizing emphasis on politics, i.e. to be able to negotiate with Israel and other countries. The PLO and the organizations within it continued to wage war on Israel for decades, but Arafat’s strategy was increasingly successful, in that the PLO gradually became the organization recognized by the UN and many countries as the group to negotiate with politically.

Through the 70’s and 80’s, Fatah and other groups within the PLO, such as Black September, as well as the PLO itself, continued to wage terrorist and guerrilla war against Israel. Their attacks were sometimes against third parties, and often against civilians, making the PLO a standard go-to villain in popular culture. Among their most famous attacks were:

The Munich Olympics Massacre (1972) Attack that killed 11 members of the Israel Olympic team and a German policeman. (Black September, a PLO Faction)

The Entebbe Hijacking (1976) Hijacked an Air France plane and took it to Entebbe, Uganda where it was held hostage. Uganda wasn’t a passive participant. Idi Amin knew of the hijacking in advance, personally welcomed the hijackers to Uganda, and supplied troops to guard the plane. Of the 248 who were kidnapped, all of the non-Israelis who were not crew members were released by negotiation. All but three of the remaining Israeli passengers were rescued by Israeli commandos who killed all of the hijackers plus 45 Ugandan troops, and destroyed several Ugandan Air Force planes on the ground to avoid the possibility of pursuit. Because Kenya had supported the Israeli effort, Amin ordered the killing of all Kenyans in Uganda. About 245 were killed and 3,000 fled the country. (Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine working with the PLO and German RZ terrorists)

Coastal Road Massacre (1978) Terrorists landed on the Israeli coast and hijacked a bus. Resulted in 38 Israeli civilian deaths. (PLO)

Achille Lauro Hijacking (1985) Hijacking of the Italian Cruise Ship Achille Lauro. The hijackers killed a wheelchair-bound American (Jewish) passenger by throwing him off the boat into the sea. (Palestine Liberation Front, a PLO faction)

Attack on the Chez Jo Goldenberg restaurant in the Marais district of Paris (1982) A splinter group of the PLO killed six people in a surprise attack on this Paris restaurant. (Abu Nidal associated with the PLO)

Today, Fatah has become primarily a political party that controls the government of the West Bank. They formerly controlled Gaza, but lost out to Hamas in 2007. Hamas had formerly been primarily a political party, but has moved radically toward terrorist attacks on Israel, so in a sense the two parties have moved in opposite directions, Fatah and the PLO towards political legitimacy, and Hezbollah and Hamas away from political legitimacy towards terrorism.

Hezbollah, likewise, has moved from being primarily a local political party in Lebanon to being primarily a trans-national terrorist organization supporting Arab causes outside of Lebanon.

Less Impartial: The Threat

The material above is as close to factual as I have been able to make it. It may have errors and inadequacies–please feel free to let me know–but the intention is to present just the indisputable facts.

It is difficult to objectively describe the expressed intentions of the non-state actors and the Arab states toward Israel without sounding partisan. For one thing, politicians everywhere make self-contradictory statements and say all kinds of things that they don’t really mean to appeal to the crowd. You have to pick and choose. Therefore, the contents of this section may not be quite as indisputable.

That said, officials of even the stodgier states have frequently expressed desire and intention to “Wipe Israel off the map”, “Eliminate Israel”, and “Destroy the Zionist Entity”, etc., over decades. Semi-official, state controlled, newspapers and radio are often explicitly genocidal. Non state entities like Hezbollah, Hamas, Fatah, and the PLO have made their genocidal intentions clear, loudly demanding that all of what was Palestine be made Jew-free.

Talk is cheap, but both the states and the non-state actors have backed up the talk with action for seventy years. Multi-nation coalitions have fought four conventional wars with the goal of destroying Israel, and reliably backed non-state actors with support, safe havens, and weapons for terrorist attacks and guerrilla war since 1948.

Clearly, the anti-Jew/anti-Israel talk is clearly not just rhetorical exaggeration–there has been an official policy across the region for more than three generations to destroy Israel.

The River to The Sea

Reasonable people can favor a return to the original UN proposal of a two-state solution or something very much like it. This the solution most widely favored among non-Middle East powers.

Likewise, reasonably people could say that a two-state solution is not possible today, but might become so in the future, and call for some better interim arrangement than Israel occupying the captured Arab territories.

Reasonable people could (and often do) say that allowing settlements in the West Bank is wrong. Other people say that Israel has been attacked too often, and Israel should abandon any hope of a two-state solution and integrate the West Bank into Israel. A completely different, approach that a non-insane person could advocate is merging the Israeli-occupied Arab territories with the Arab countries that are adjacent to them, i.e., Jordan takes the West Bank and Egypt takes Gaza.

Saying that a proposal is reasonable doesn’t mean that it is morally right, or fair, or practical–only that it’s something a person of good faith could legitimately argue for.

What reasonable people cannot do is support Arab rhetoric demanding an Arab Palestine “From the river to the sea.” Why? For many reasons, but the one that cannot be gotten past is that the Palestinian leadership, not just Hamas and Hezbollah, but essentially all of the leadership going back to 1948, has loudly and sincerely advocated genocide of the Jews, and the surrounding Arab states have often enthusiastically agreed and militarily promoted that goal. It was never just talk; they gave it their best shot repeatedly.

The slogan does not advocate a political change–it advocates ethnic cleansing and the extinction of Israel. To repeat that slogan is villainous and shameful. No decent person should tolerate it in their presence any more than they would tolerate Nazi talk or KKK gibberish.

How Great Questions are Settled

The war of 1948 decided the question of whether there would be a Jewish state. But Israel’s victory did not decide the question of whether or not there would also be an Arab state in the Mandated Palestine. Transjordan decided that question in the negative for at least the next generation when they annexed the West Bank.

In doing so, they hijacked the most important part of what might have been Arab Palestine. Even had the Israelis lost the war, it would have been highly improbable that anything like the Arab Palestine dreamed of in 1947 would ever have come about, because Transjordan managed to dismember Palestine even when they lost the war. The intransigence of Jordan over the next 19 years made achieving peace in the future even more difficult because by 1967 an entire generation of Palestinians had been raise to be implacably anti-Israel, and the attack made it clear that the West Bank provided an important buffer against attack from Jordan.

The American Civil War settled the question of whether the United States was to be a country, or just an alliance of convenience, like the European Union. There was no middle ground; it had to be one or the other, and there was no higher authority to arbitrate. The decision was written in the blood of half a million Americans. America does not continually revisit this question. It is a done deal.

The question in 1947 was the same kind of issue. There was no meaningful middle ground. The Jewish citizens of Palestine voted that the territory proposed by the UN would become a Jewish state; Israel chose to exist. The Palestinian Arabs voted that Israel would not exist, insisting that the entire territory would be an Arab nation, and they chose to fight for it. As in the American Civil War, there was no higher authority, no indisputable principle to appeal to. The League of Nations and subsequently, the United Nations had advocated a two-state solution but could not impose it. The issue was settled by war. It is a done deal.

The argument that the Jews don’t have a right to be on “traditionally Arab land” depends on the indefensible idea that immigrants do not have the right to become full citizens of their new land. I don’t know of anyone, in any country, who is not on the ultra-nationalist far right, who believes this as a general proposition.

This is an idea that is applied solely to Jewish Israel. Approximately 97% of the people of the United States are either immigrants or descend from immigrants. Most of Western Europe is slowly filling with immigrants from foreign lands, and once they are citizens, they get to vote like anyone else; one person, one vote.

The Prime Minister of England is a Hindu, an ethic Indian who’s parents immigrated from East Africa in the 1960’s. But he’s a Brit now. New immigrants in the United States routinely decide our national elections. Florida has repeatedly been the critical state in presidential elections, and it is first and second generation Cuban immigrants who decide how Florida will go. They aren’t Cubans now–they’re Americans.

Is Israeli policy in the West Bank and Gaza just? Should the “settlements” in the West Bank be allowed? Who should decide? I don’t know, and neither, in all likelihood, does anyone reading this. But I do know that the experience of many centuries tells the Jews of Israel that when people scream for their blood, it is not just hyperbole.

War is hideous, and it kills mostly civilians. All wars. But it is not the Israelis who chose this war against Hamas. Hamas chose to open the conflict with such outrages specifically so that decent people could not do anything other than go to war. What kind of person sees this happen and waves a Hamas flag? Nobody I will eat or drink with, I can tell you.